7.7. Chapter Summary#

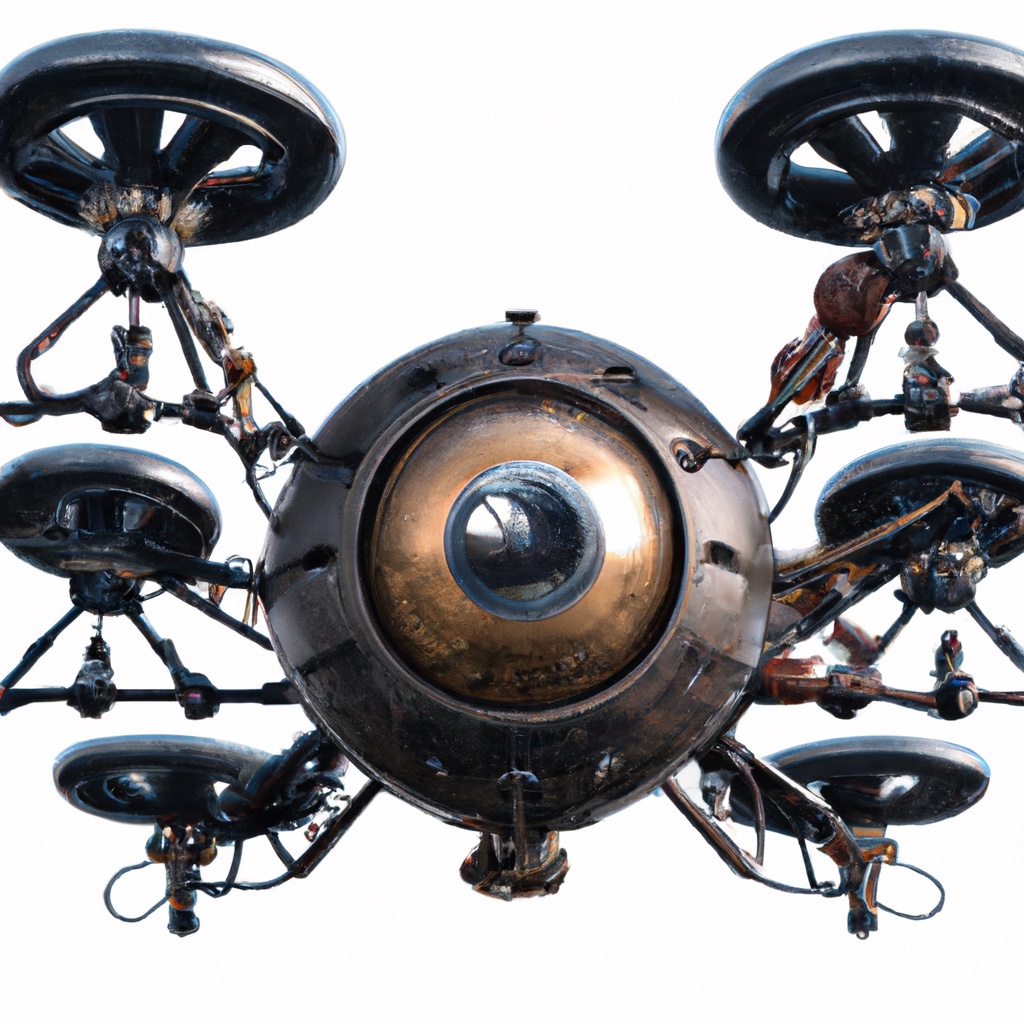

In this final chapter, we upgraded to moving in 3D spaces, and explored an under-actuated autonomous system: a quadrotor drone. Flying a drone needs some physics but this drone design is popular especially because the kinematics and dynamics are relatively simple. We discussed both advanced perception and planning methods that are frequently used in a drone context.

7.7.1. Models#

Drones move in 3D, so we resolutely moved to rigid transformations in three dimensions as describing the state of the drone, along with its linear and angular velocity. We introduced the \(SE(3)\) manifold, which looks almost identical to \(SE(2)\), but with a twist: rotations in 3D no longer commute. But from a practical point of view, rigid transformations in 3D are not much harder to deal with than in the 2D case.

The action space for drones is four-dimensional, corresponding to the four thrust vectors generated at the four rotors. Maintaining hover is straightforward and gave us some ideas about how to specify the desired forces, given a certain mass. We then explored forward flight and the relationship between tilt and forward velocity. Simulation of the drone’s kinematics needed some interesting facts about 3D rotations, specifically the closed-form Rodrigues’ formula, which allowed us to translate angular velocity into incremental rotations over time. Finally, dynamics was introduced to think about forces and torques, and the associated equations of motion.

Compared to full rigid-body dynamics, we kept the exposition on sensing for drones relatively light. We did introduce an important new sensor: the IMU or inertial measurement unit. A typical IMU consist of a gyroscope, accelerometer, and magnetometer, and when used expertly, it is a very valuable sensor. However, there are tricky calibration and bias issues that make this one of the most difficult sensors to integrate. Luckily, another useful sensor for drones is the camera: in Section 7.2 we discussed using two cameras in a stereo configuration. A nice property of a stereo camera is that it allows us to measure points in 3D, but in a much more efficient way than a LIDAR.

7.7.2. Reasoning#

In the perception section, we explored Visual SLAM as an advancement of “SLAM with Landmarks” by incorporating 3D poses and points. We emphasized the use of cameras in unmanned aerial vehicles due to their energy efficiency and compact size. Additionally, we introduced methods for trajectory estimation using IMUs and discussed constructing 3D maps from images using structure from motion (SfM). Visual SLAM integrates these technologies into a real-time, incremental pipeline. While the implementation details of Visual SLAM are beyond the scope of this book, its potential for enabling autonomous flight through simultaneous inertial sensing and 3D reconstruction should be clear.

In Section 7.5, we shifted focus to trajectory planning for drones moving in 3D. To achieve optimal trajectories, which are critical for efficiency in time, energy, or distance, we introduced trajectory optimization. We began with the fundamental query of navigating from point A to B, illustrating the complexity introduced by factors such as drone attitude and varying speeds at start and end points. We then expanded upon the details needed for optimizing trajectories: defining the goal and representing environments with cost maps that account for obstacles. Once again, we used GTSAM and factor graphs to state the resulting optimization problem and solve it. After discussing time interpolation, we outlined a cascaded controller using drone kinematics and dynamics to execute these trajectories.

Finally, in the last section of the book, we focused on learning 3D representations from image data, specifically addressing the challenge of navigating new environments. Building on previous discussions about sparse SfM and its limitations, we introduced a learning-based approach for creating detailed dense 3D scene models. We introduced Neural Radiance Fields (NeRF), a recently introduced neural-based method for realistic scene rendering, which supports motion planning and obstacle avoidance in drones. We also discussed the possibility of integrating NeRF’s density fields with motion planning techniques to enhance autonomous navigation in drones. However, note that neural scene representations are a fast-evolving field, and the details in this section might not stand the test of time, even if the intended application is expected to be served even better.

7.7.3. Background and History#

The idea of using four rotors for vertical take-off and landing (VTOL) capabilities is even older than conventional helicopters, as evidenced by the full-scale contraption built by De Bothezat in 1921. This early work was ultimately not successful, but of note is another attempt for a full-scale aircraft based on this principle called the X-22A by Bell. The application of essentially the same principle for small unmanned aircraft can probably be attributed to the 1999 HoverBot project at the University of Michigan, led by Johann Borenstein. You can easily find video clips associated with each of these online.

A good contemporary overview on “multirotor aerial vehicles” is the review article by Mahony et al. [2012]. The kinematics and dynamics in 3D were inspired by the book [Murray et al., 1994] and the more recent and excellent “Modern Robotics” textbook by Lynch and Park [2017]. A more general treatment of small unmanned aircraft is [Beard and McLain, 2012], which is focused more on fixed-wing aircraft but treats many aspects of MAVs in more depth.

Regarding perception with IMUs, a recent text on inertial sensing and navigation is [Farrell, 2008]. The pre-integration of IMU measurements into binary factors was introduced by Forster et al. [2016], inspired by an earlier paper by Lupton and Sukkarieh [2012]. Structure from Motion aka 3D reconstruction from images is an old topic in computer vision, and for a deep dive two books come highly recommended: [Hartley and Zisserman, 2000] and [Ma et al., 2004].

As mentioned, the controller in Section 7.5 was inspired by [Gamagedara et al., 2019]. The idea of combining a controller with Neural Radiance Fields (NeRF) was presented in a 2022 Stanford paper by Adamkiewicz et al. [2022], and Section 7.6 on NeRF drew mostly on the original paper by Mildenhall et al. [Mildenhall et al., 2021] as well as the later, voxel-based variant in the Direct Voxel Grid Optimization (DVGO) paper by Sun et al. [2022].